Asset Allocation for Beginners: A Calm, Powerful Reality Check 🧭

Asset Allocation for Beginners can feel confusing in 2026—especially when stocks and bonds don’t behave the way the old “rules” promised. This guide is a practical reality check: you’ll learn how to build a simple core portfolio, avoid the most expensive allocation mistakes, and use clear rebalancing rules that keep you calm when markets get weird.

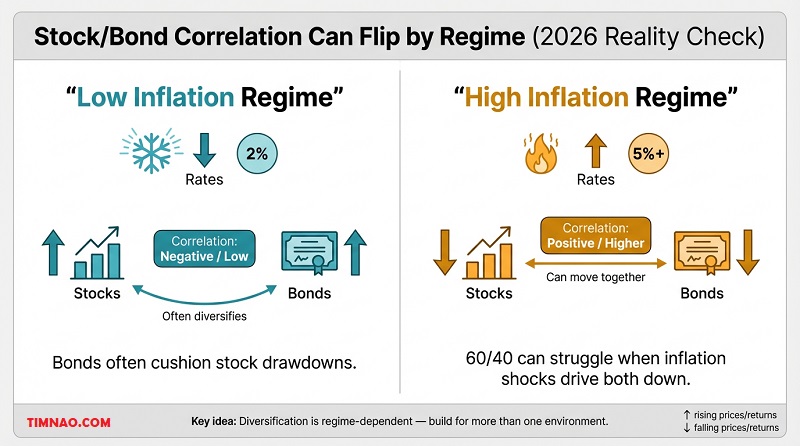

Why asset allocation feels “broken” in 2026: stock/bond correlation and regimes

If you’re googling asset allocation for beginners, you’ve likely seen hot takes like “60/40 is dead,” “bonds are pointless,” or “just add crypto and you’re diversified.” The useful truth is quieter: the market doesn’t behave the same way in every environment.

Asset allocation feels “broken” in 2026 because many people learned diversification during the 2010s (when inflation was calm and rates mostly fell), then lived through an inflation-and-rate-shock stretch where the usual relationships changed. When the “rules” shift, a portfolio that felt stable can suddenly feel confusing.

The stock/bond correlation flip (and why it matters)

Sometimes stocks and bonds move like a seesaw… and sometimes they move like they’re tied together.

- In many low-and-stable inflation periods, bonds often helped when stocks fell. Rates dropped, bond prices rose, and your portfolio had a cushion.

- In inflation-surprise periods, rates can rise while stocks fall. Bond prices drop at the same time stocks drop—so the cushion doesn’t behave the way you expected.

This is why “bonds are safe” is only half true. Bonds have their own main risk: interest-rate risk (duration). When rates rise fast, longer-term bonds typically fall more than short-term bonds. That’s not a weird exception—it’s the mechanism.

Regimes: the market isn’t on one permanent setting

Markets behave differently depending on the dominant problem of the moment. Call these “regimes”:

- Growth regime: “Is the economy speeding up or slowing down?”

- Inflation regime: “Is inflation sticky, and how tough will policy get?”

- Stress regime: “Who needs liquidity right now, and where is the hidden leverage?”

You don’t need to forecast regimes like a pro. You just need a portfolio that isn’t built for only one regime.

A beginner-friendly mental model:

- Stocks are your long-term growth engine.

- Bonds can be income + ballast, but they’re sensitive to rate moves.

- Cash (and short-term bonds) are your “life-happens” buffer.

- Everything else (gold, commodities, trend, crypto, private assets) is a tool—never a magic shield.

Why 60/40 feels questionable (even when it isn’t “dead”)

When people say “60/40 doesn’t work,” they usually mean one of these:

- They expected bonds to always go up when stocks go down.

That expectation can fail in inflation-driven selloffs. - They held more long-duration bond risk than they realized.

Two “bond funds” can act totally differently if one is short-term and the other is long-term. - They never defined what “works” means.

If “works” means “never has a bad year,” nothing works. A better standard is: “Can I stay invested, keep contributing, and avoid panic decisions when things get ugly?”

The beginner trap: reacting to a regime shift with random new assets

When the classic mix disappoints, the internet offers replacements: private credit, private equity, “all-weather” strategies, crypto, leveraged products, or niche thematic ETFs. The danger isn’t that all of these are bad. The danger is adding them as a reaction—without a role, without sizing rules, and without a plan for the downside.

Before you add anything “new,” ask one sentence:

“When does this help, and what pain am I paying for that help?”

If you can’t answer clearly, you’re buying a story.

The reality baseline: what asset allocation can and can’t promise

Let’s reset expectations so you can build something you’ll actually stick with.

What asset allocation is (in real life)

Asset allocation isn’t a single “best portfolio.” It’s how you split money across big risk buckets—typically:

- stocks (growth risk)

- bonds (rate + credit risk)

- cash/short-term reserves (liquidity)

- optional diversifiers (inflation sensitivity, crisis behavior, alternative payoffs)

This mix becomes your default behavior when you’re not thinking about investing every day. It’s also why two people can own the same index fund and still get different outcomes: their overall mix (and their ability to stay invested) is different.

What asset allocation can reasonably do for you

For beginners, the best promise of asset allocation isn’t “higher returns.” It’s better control over the reasons people quit.

A solid allocation can help you:

- limit drawdowns to a level you can tolerate

- reduce the chance of panic-selling

- match risk to timeline (soon money vs. later money)

- make contributions easier because the plan feels survivable

It doesn’t promise you’ll avoid losses. It helps you avoid the kind of loss that makes you abandon the plan.

Asset allocation cannot:

- guarantee profit

- eliminate bad years

- protect you from every scenario

- replace savings rate, debt control, and emergency cash

- turn speculation into a plan

If someone claims they have a portfolio that “wins in every market,” they’re either overselling, hiding risk, or ignoring costs.

The beginner distinction that changes everything: end-of-horizon vs. “within-horizon” pain

Most people think about risk like this: “Will I be up after 10 years?”

But real investors experience the journey. A portfolio can be “fine long-term” and still put you through a drawdown that breaks your discipline halfway through.

So add a second question:

“Can I live through the worst year on the way to my goal?”

Mini-example (3–6 lines):

- You plan to invest for 15 years.

- Year 4 hits and your portfolio drops 25%.

- If you panic-sell, your long-term plan ends right there.

- A slightly more conservative mix might keep you investing and buying through the dip.

A simple baseline you can apply today

If you want an allocation that’s usable in 2026 (without needing a prediction), start with these rules:

- Separate “soon money” from “later money.”

Money you might need in 0–3 years shouldn’t be forced to take stock-level risk. - Pick a stock/bond split you can hold under stress.

If you’re unsure, go a bit more conservative than your bravest fantasy-self. - Keep a real liquidity buffer.

Cash isn’t “wasted” if it prevents debt, forced selling, or sleepless nights. - Add complexity only when the basics are stable.

New assets should solve a specific problem (inflation, drawdown behavior, liquidity), not boredom.

How to tell if your baseline is realistic

Quick self-check:

- If your portfolio dropped 20% in a year, would you keep contributing?

- If stocks and bonds both fell for a while, are your cash needs covered?

- If you were busy for 12 months, would you still understand what you own?

If any answer is “no,” that’s not failure. It’s a signal to simplify, shorten bond duration, raise cash reserves, or reduce risk until the plan fits your real life.

And that’s the point: asset allocation isn’t broken. The old shortcuts are broken. Next, we’ll turn this baseline into simple IF/THEN rules you can follow when the market tries to mess with your head.

12 IF/THEN rules that prevent the most expensive allocation mistakes

If Part 1 gave you the “why,” this section gives you the “what to do when your brain starts negotiating with the market.”

These aren’t theory rules. They’re damage-control rules—the kind that stop beginners from making expensive, emotional changes at exactly the wrong time.

A quick note before we start: these rules aren’t meant to make you “perfect.” They’re meant to make you consistent, which is the only superpower most investors actually need.

The trap: “This person is smart and their portfolio worked, so I’ll do the same.”

Why people fall for it: It feels like a shortcut. No math. No uncertainty. Just follow the “pro.”

The real cost: You copy the output (weights) without the inputs (time horizon, cash needs, tax situation, job stability, stomach for volatility). So when the portfolio hits a rough patch, you don’t know what it’s supposed to do—and you bail.

Do this next:

- Write down your 3 inputs: time horizon, cash needs (next 24 months), max drawdown you can tolerate.

- Only copy a portfolio if it fits those inputs. If not, copy the structure (simple core + rules), not the weights.

Rule 2 — IF your plan assumes “bonds will always protect me,” THEN split bonds into jobs (not one bucket)

The trap: Treating “bonds” as one thing.

Why people fall for it: Beginners are told “bonds = safer,” so they buy one bond fund and move on.

The real cost: In rate shocks, long-term bonds can fall hard. In credit stress, lower-quality bonds can behave more like stocks. If you don’t know which bond risk you own, you’ll be surprised when your “safe” side drops.

Do this next:

- Give bonds clear roles:

- Short-term / cash-like: stability and liquidity

- Intermediate: balance of income + rate risk

- Long duration: can help in some recessions, but hurts in fast rate rises

- As a beginner, lean toward short-to-intermediate until you truly understand duration.

Rule 3 — IF you can’t explain an asset’s “bad day,” THEN don’t size it big

The trap: Buying something because it has a nice story: “uncorrelated,” “inflation-proof,” “all-weather.”

Why people fall for it: People focus on the upside or the sales pitch.

The real cost: The asset disappoints in the exact moment you expected it to save you—then you sell at the worst time.

Do this next:

- For every major holding, answer:

- “What scenario makes this fall?”

- “How much can it fall in that scenario?”

- If you can’t answer, keep it small (a “satellite”), or keep it out for now.

Rule 4 — IF you’re adding a new asset because the old one disappointed, THEN wait 14 days and re-check the reason

The trap: “Stocks/bonds didn’t work, so I need a new thing.”

Why people fall for it: Pain creates urgency. Urgency creates bad decisions.

The real cost: You chase whatever recently looked good (often after it already ran), then end up with a messy portfolio you don’t understand.

Do this next:

- Write a one-sentence reason: “I’m adding X because it helps when ______ happens.”

- Wait 14 days. If the reason still holds and you understand the downside, proceed. If not, you were just reacting.

Rule 5 — IF you own more than 5–7 funds, THEN run a redundancy check before adding anything else

The trap: Confusing “more funds” with “more diversification.”

Why people fall for it: It’s easy to collect funds like Pokémon—each one sounds unique.

The real cost: You pay more fees, make rebalancing harder, and accidentally overweight the same risk (usually U.S. growth stocks) in multiple wrappers.

Do this next:

- Do a simple grouping:

- Stocks (U.S., international, small, value)

- Bonds (short, intermediate, long, credit)

- Real assets / gold / commodities

- Alternatives / crypto

- If two funds live in the same box, keep the cheaper/simpler one.

Rule 6 — IF your allocation changes every time you read the news, THEN your “strategy” is actually a mood tracker

The trap: “I’ll adjust as new information comes in.”

Why people fall for it: Sounds responsible. Feels adaptive.

The real cost: You end up buying high, selling low, and constantly second-guessing. Even if you’re right sometimes, the habit is exhausting—and that’s usually what breaks people.

Do this next:

- Pick one review rhythm:

- Calendar rule: review every 6 months

- Band rule: rebalance only if something drifts beyond a preset band (example: ±5%)

- Outside that rule, don’t touch the allocation unless your life changed (job, cash needs, timeline).

Rule 7 — IF you’re “long-term,” THEN define a mid-journey pain limit (because that’s when people quit)

The trap: “Time will smooth it out.”

Why people fall for it: Charts often show long-term averages, not what it feels like to live through drawdowns.

The real cost: You hit a scary drawdown mid-way, panic-sell, and never get the long-term benefit you were counting on.

Do this next:

- Pick a realistic “I can still sleep” drawdown number (example: -15%, -25%, -35%).

- Build your stock/bond/cash mix to match that number.

- Write it down: “I expect drawdowns up to X%. I won’t change the plan unless my goals change.”

Rule 8 — IF you have important spending in the next 1–3 years, THEN treat that money as a separate portfolio

The trap: One portfolio for everything.

Why people fall for it: Simplicity. Also, beginners underestimate how fast “future plans” become “next month.”

The real cost: You’re forced to sell risky assets during a downturn to pay for real life.

Do this next:

- Create two mental buckets (even if it’s the same account):

- Soon money (0–3 years): cash + short-term, stable assets

- Later money (3+ years): growth assets like stocks (plus bonds as needed)

- Don’t gamble with the money you’ll need on a deadline.

Rule 9 — IF you’re considering illiquid assets, THEN size them by liquidity needs, not by return dreams

The trap: “Private assets are smoother and higher return.”

Why people fall for it: The line looks calm. The pitch sounds exclusive.

The real cost: Illiquid assets can trap you. When you need cash, you can’t sell. When you want to rebalance, you can’t move weight. And “smooth returns” can be partly an illusion of infrequent pricing.

Do this next:

- Build a liquidity runway first (cash + liquid bonds).

- Cap illiquids at a level where you can still handle emergencies without selling them.

- Assume illiquids are riskier than they look and plan accordingly.

Rule 10 — IF you’re using an optimizer or “perfect weights,” THEN replace precision with ranges

The trap: “This spreadsheet says 63% stocks is optimal, so I’ll do exactly 63%.”

Why people fall for it: Precision feels scientific.

The real cost: Tiny changes in assumptions can produce totally different “optimal” portfolios. That leads to constant tweaking, confusion, and regret.

Do this next:

- Use weight ranges like a grown-up:

- Stocks: 50–70%

- Bonds: 20–45%

- Cash: 0–15% (depending on needs)

- Then choose a point inside the range you can stick with. Consistency beats “optimal.”

Rule 11 — IF you add crypto, THEN size it by risk (not by how exciting the upside feels)

The trap: “I’ll put 10–30% in crypto because it could change my life.”

Why people fall for it: The upside narrative is strong, and people anchor to past bull runs.

The real cost: Crypto volatility can dominate your entire portfolio risk. Even a “small” allocation can feel huge when it swings hard—then you panic-trade.

Do this next:

- Treat crypto as an experimental sleeve, not your foundation.

- Start small enough that a 50–80% drawdown wouldn’t wreck your plan.

- No leverage. No borrowing. No “I’ll just add more if it drops” unless you pre-committed with rules.

Rule 12 — IF you can’t secure it, THEN don’t own it (especially for crypto)

The trap: “I’ll figure security out later.”

Why people fall for it: Security is boring—until it’s catastrophic.

The real cost: Phishing, fake apps, SIM swaps, exchange issues, sending funds to the wrong address—many mistakes are irreversible.

Do this next:

- Basic hygiene (beginner-safe):

- Use strong 2FA (avoid SMS when possible).

- Don’t click login links from messages; type the site manually.

- Never share recovery phrases. Ever.

- If you’re using major platforms, stick to official homepages like Coinbase or Binance and bookmark them—no random links, no “support DMs.”

At this point, you’ve got the guardrails—the rules that stop the biggest allocation mistakes before they happen. Next, we’ll shift from “what not to do” to what actually works in practice: how to build a simple core portfolio, rebalance without stress, and add diversifiers only when they earn a job in your plan.

Time diversification fallacy: the “within-horizon loss” problem most plans ignore

If you’ve ever heard “stocks are risky short-term but safe long-term,” you’ve met the time-diversification story. It’s comforting, and it’s not totally wrong — but beginners often absorb it in a dangerous way: they think time magically deletes risk.

Time doesn’t delete risk. Time only gives your portfolio more chances to recover — and also more chances to scare you into quitting.

Here’s the missing piece most investing advice skips:

- End-of-horizon risk asks: “Am I likely to be up after X years?”

- Within-horizon risk asks: “At any point during those X years, how bad could it get?”

Most people don’t fail investing because the final outcome was mathematically impossible. They fail because the journey was emotionally impossible.

Why “longer horizon = safer” can be misleading

When you extend your horizon from 1 year to 10 years, two things happen at once:

- You increase the chance that markets eventually bounce back.

- You also increase the chance that you experience at least one big drawdown along the way.

So even if “the odds of being up in year 10” improve, “the odds of seeing a gut-punch at some point” can also rise.

A beginner-friendly analogy:

- Crossing a river once is risky.

- Crossing it ten times gives you more chances to make it safely… and also more chances to slip and fall.

Investing is similar. If you only measure success at the final checkpoint, you can ignore the times you nearly quit. But your emotions don’t ignore them.

The practical consequence: portfolio design should match your “quit point”

Most people have a personal quit point — a level of loss that triggers panic, a need to “do something,” or an urge to go to cash “until things feel better.”

You don’t need to feel ashamed about that quit point. You need to design around it.

Try this 60-second exercise:

- Imagine your portfolio drops 20% in six months.

- Imagine it drops 35% in a year.

- Which number makes you feel like you would change the plan?

That number is a clue. Asset allocation is partly a math problem, but it’s also a behavior problem.

A tiny walkthrough: end-of-horizon vs within-horizon

Let’s say you invest $10,000 for 15 years.

- Investor A: “I’m young. I’ll do 100% stocks.”

- Investor B: “I can’t handle huge swings. I’ll do stocks + bonds + cash.”

Year 4: markets fall hard.

- Investor A sees -35% and sells. Now they have “avoided risk” — but they’ve also locked in the loss.

- Investor B sees -18% and keeps contributing. They feel uncomfortable, but not panicked.

Fifteen years later, Investor B may end up ahead simply because they stayed in the game. That’s the hidden advantage of an allocation that fits your nerves.

What to do instead: build a “drawdown-aware” plan

If you want a simple, modern fix (especially for 2026-style uncertainty), use these three guardrails:

Guardrail 1: Separate time horizons.

- Money needed in 0–3 years: keep it boring (cash, short-term bonds).

- Money needed in 3–10 years: balance growth and stability.

- Money needed in 10+ years: you can take more equity risk — but still with rules.

Guardrail 2: Pick a maximum drawdown target.

Not a performance goal. A pain goal.

- “I can live with -15%.”

- “I can live with -25%.”

- “I can live with -35%.”

Then choose an allocation that makes that pain level plausible, not rare.

Guardrail 3: Pre-commit to what you do during a drop.

Write one sentence you can follow when your brain gets dramatic:

- “If my stocks fall, I rebalance on schedule.”

- “If I feel the urge to sell, I wait 72 hours and reread my plan.”

That’s not motivational fluff. It’s a circuit breaker.

By the way, this is why “aggressive” isn’t always brave. Sometimes the bravest move is choosing a portfolio you can actually hold.

Illiquidity and appraisal smoothing: why private assets can look safer than they are

Private assets are having a moment: private equity, private credit, private real estate, venture, “evergreen” funds, interval funds, and all kinds of semi-liquid products. The marketing pitch often sounds like this:

- “Higher return.”

- “Lower volatility.”

- “Low correlation.”

- “Access what institutions buy.”

The problem is that two of those claims can be true on paper while still misleading in practice — especially for beginners.

The core issue: private assets don’t “wiggle” as often on your screen

Public markets update prices constantly. Private markets often update prices infrequently, using appraisals or models.

That creates appraisal smoothing:

- returns look calmer,

- volatility looks lower,

- drawdowns look smaller or delayed.

But the real economic risk can still be there — it just isn’t showing up every day as a price change.

A beginner analogy:

- If you only weigh yourself once a month, your weight chart will look smoother.

- That doesn’t mean your body changed smoothly; it means you measured less often.

The second issue: liquidity is a risk, not a feature

Illiquidity isn’t just “can’t sell quickly.” It’s a bundle of real constraints:

- you may have lockups,

- you may have gates or redemption limits,

- you may face pricing that’s stale during stress,

- you may be forced to accept a bad price if you must exit.

In normal times, illiquidity can feel like stability. In stressful times, it can feel like a trap.

The beginner mistake: sizing private assets like they’re “bonds with extra yield”

Some people treat private credit as “safer than stocks, better than bonds.” That’s a dangerous mental shortcut.

Private credit can carry:

- default risk,

- liquidity risk,

- valuation opacity,

- and sometimes leverage inside the fund structure.

That doesn’t make it bad. It makes it not a cash substitute.

A simple “private assets readiness” checklist

Before allocating a meaningful amount to illiquid assets, ask:

- Do I have a liquidity runway?

Can you cover 6–24 months of likely needs without selling risk assets? - Do I understand the rules of the product?

Lockups, redemption windows, gates, fees, and how valuation works. - Can I hold through a long “boring” period?

Private funds can underperform for years. If you’ll chase performance, don’t go illiquid. - Can I rebalance without it?

If stocks crash, can you rebalance using liquid assets? If not, your overall portfolio may drift in ways you didn’t plan.

If any of these are “no,” the most practical move is to stay simple and liquid until the basics are rock-solid.

How to include private assets without fooling yourself

If you do want private exposure in a beginner-friendly way, these rules reduce regret:

- Assume private equity behaves like equity risk.

Don’t size it like “safe income.” Size it like “risky growth.” - Treat reported volatility as a floor, not a ceiling.

Smooth charts don’t mean smooth outcomes. - Make liquidity a first-class constraint.

Decide your maximum illiquid percentage based on your cash needs, not on expected returns.

Mini-example (simple sizing rule):

- You want a 12-month emergency fund and also might pay for a home down payment in 2 years.

- That’s a strong signal to keep private allocations small (or zero) until those goals are funded in liquid assets.

A 2026-style reality check: semi-liquid doesn’t mean liquid

Many products sit in the middle: “monthly liquidity,” “quarterly redemption,” “interval funds.” In calm markets, they can feel liquid. In stressed markets, the rules matter — and the rules usually protect the fund, not you.

As a beginner, you don’t need to win the private market game. You need to avoid getting stuck.

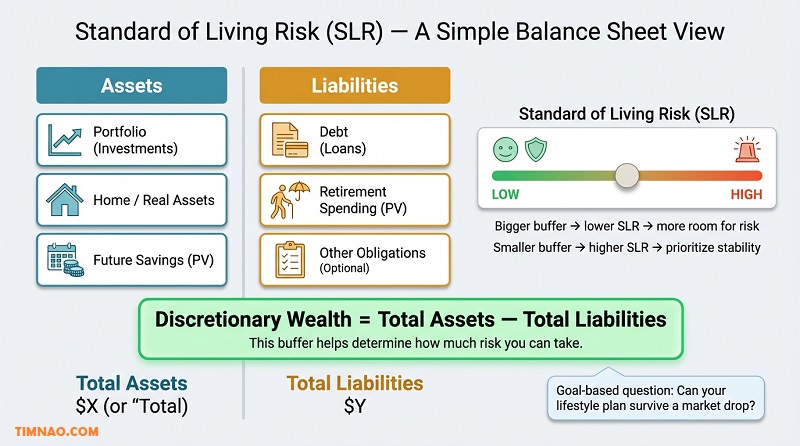

Standard of living risk (SLR): a goals-based way to pick risk without guesswork

Most beginners pick risk backwards. They start with a portfolio (often from a chart), then hope it matches their life.

A goals-based approach flips it:

- Start with your life.

- Then choose the risk you can afford.

That’s the spirit behind standard of living risk — the idea that the real risk isn’t “volatility,” it’s failing to fund the life you want.

The simplest way to understand SLR

Think of your future lifestyle as a bill you must pay.

Your portfolio plus future savings are what you’ll use to pay it.

So the question becomes:

- “How much risk can I take without putting my lifestyle goal at serious risk?”

If your plan is already fragile (low savings buffer, high obligations, uncertain income), then taking more risk doesn’t always help. Sometimes it increases the chance of a plan-breaking drawdown.

A beginner-friendly SLR mini-template

You can do this on paper in 10 minutes.

Step 1: List your ‘must-protect’ needs (next 2–3 years).

Examples:

- rent/mortgage

- insurance

- family obligations

- tuition

- medical buffer

Step 2: List your big lifestyle goals (5–30 years).

Examples:

- retirement income

- home purchase

- education funding

- financial independence target

Step 3: Score your buffer (1–5).

Give yourself a score on:

- savings rate (higher = better buffer)

- job stability (higher = better)

- flexibility to cut expenses (higher = better)

- debt burden (lower = better buffer)

Now interpret it:

- Strong buffer: you can take more equity risk, because you can survive drawdowns without changing your life.

- Weak buffer: you need more liquidity and a smoother ride, even if returns might be lower.

This doesn’t require spreadsheets. It requires honesty.

How SLR changes your asset allocation decisions

SLR pushes you toward three practical behaviors:

- Protect the floor first.

Before chasing upside, make sure you can pay the bills without selling risk assets in a downturn. - Match risk to the fragility of the goal.

A goal that must happen on a deadline (home down payment in 2 years) needs a safer allocation than a goal that can flex (retire at 60 vs 62). - Use contributions as your “risk lever,” not only your allocation.

If you have a strong savings rate, you can often take less portfolio risk and still reach goals. Many beginners ignore this and try to “invest their way out” instead of saving.

Mini-scenario:

- Person A saves 25% of income and invests moderately.

- Person B saves 5% and invests aggressively.

Person A often wins in real life, because savings rate is a controllable input.

A simple SLR-based allocation guideline

If you want a usable rule of thumb, try this:

- If your next 2 years have big obligations: increase cash/short-term reserves; keep stocks lower.

- If your income is unstable: prioritize liquidity and simplicity.

- If your buffer is strong and timeline is long: you can afford more stocks, but still avoid complexity until you can manage it.

SLR doesn’t tell you one perfect portfolio. It tells you what kind of portfolio won’t break your life.

Estimation error: how to stop optimizers (and gurus) from whipsawing your portfolio

Here’s a secret that makes investing feel less confusing: most “precise” portfolio recommendations are built on numbers that are not precise.

Expected returns are uncertain.

Correlations change.

Volatility clusters.

And the future rarely matches the clean historical sample that produced a backtest.

This is estimation error — and it’s why optimizers and gurus can push you into constant portfolio changes.

Why optimizers can produce silly portfolios

A classic optimizer tries to find the “best” weights given:

- expected returns,

- volatility,

- and correlations.

The problem: the optimizer treats your inputs like facts. But in real life, your inputs are guesses.

So the optimizer often does two unhelpful things:

- It over-weights the asset with the highest assumed return (even if that assumption is flimsy).

- It over-weights the asset with the lowest assumed correlation (even if that correlation changes in stress).

Result: you get an “optimal” portfolio that’s fragile, concentrated, and extremely sensitive to small changes in assumptions.

The guru version of the same problem

Gurus do the same thing, just with storytelling instead of math:

- “This asset will outperform for the next decade.”

- “This one is the future.”

- “This is the hedge you need.”

The issue isn’t that forecasts are always wrong. It’s that beginners often build portfolios that only work if a forecast is exactly right.

A beginner-friendly anti-whipsaw toolkit (no math needed)

You can protect yourself from estimation error with four practices:

1) Use ranges, not point targets.

Instead of “63% stocks,” use “stocks 50–70%.”

This single change makes your plan robust. You stop feeling like every drift requires action.

2) Put guardrails on concentration.

Even if you love an idea, cap it.

- single theme/sector: small

- single alternative: small

- experimental assets: small

You can be right and still get hurt if you size it wrong.

3) Prefer simple, explainable exposures.

Broad index funds are boring for a reason: they remove a lot of estimation risk. If you want extra complexity, earn it after you’ve built consistency.

If you use big fund families for broad exposure, stick to official sources like Vanguard, BlackRock, or Fidelity when you’re learning the basics.

4) Update your plan on life changes, not market narratives.

A new job, a child, a housing plan, a health change — those justify allocation changes.

A scary headline usually doesn’t.

A mini-example: how ranges stop “optimal” chaos

You run a calculator and it says:

- Portfolio X: 70% stocks / 30% bonds

Next month, with slightly different assumptions, it says: - Portfolio Y: 45% stocks / 55% bonds

A beginner sees this and thinks, “I should switch.”

A range-based investor says:

- “My stock range is 50–70%. I’m already inside it. No action.”

That’s how you avoid death-by-tweaking.

The 2026 practical stance: aim for robustness, not brilliance

In a world where regimes change and correlations can flip, robustness is a feature.

A robust portfolio is one that:

- you can explain,

- you can hold,

- you can rebalance,

- and you can live with across multiple futures.

That’s not boring. That’s professional.

From here, the next section of the article will move from “hidden risks” to “implementation that actually works”: building a simple core, rebalancing with rules, and choosing diversifiers that earn their place.

What actually works in practice: simple core, clear rebalancing, and honest diversifiers

After all the myth-busting and risk talk, this part is where things finally get… normal.

In real life, most investing success comes from a small set of repeatable habits:

- a simple core you actually understand

- a rebalancing rule you can follow when you’re busy or stressed

- a few honest diversifiers (optional) that have a clear job — not a marketing story

Let’s build that in a way that still makes sense in 2026, even if markets behave differently than they did in the 2010s.

Start with the “boring core” (it’s boring for a reason)

A core portfolio should do three things:

- Capture global growth (stocks)

- Dampen the ride (bonds, chosen intentionally)

- Keep life from forcing bad decisions (cash / short-term reserves)

For beginners, the simplest version is often a “3–4 building block” core:

- Global (or mostly global) stocks

- High-quality bonds (short/intermediate focus unless you know what you’re doing)

- Cash/short-term reserves (based on real-life needs)

- Optional: inflation-aware bond sleeve (if available and relevant)

You’ll notice what’s missing: ten “special funds,” constant tweaks, and a different asset class every month. That’s not because those things never work — it’s because they’re rarely worth the complexity for a beginner.

Stocks: pick a simple exposure you won’t abandon

For most beginners, the biggest stock decision isn’t “which stock.” It’s:

- How much stock risk can I hold without panicking?

- Do I want global exposure, or a home-country bias?

A simple approach that avoids overthinking:

- Prefer broad, diversified stock funds over themes and sectors.

- If you must tilt (small cap, value, tech, etc.), keep it small enough that you won’t touch it when it underperforms.

Mini-example (keep it practical):

- Core stock: broad market / global stock fund

- Tilt (optional): a small slice of something you believe in

If your “tilt” becomes the thing you check daily, it’s too big.

If you’re learning the basics and want to compare fund structures, stick to major providers’ official info so you don’t get sucked into affiliate content: Vanguard, BlackRock, Fidelity.

Bonds: stop treating them as one blob

Bonds are not automatically “safe.” Bonds are a toolbox. Different bonds solve different problems.

Here’s the beginner-friendly version:

- Short-term high-quality bonds: stability and “don’t make it worse” behavior when rates move fast

- Intermediate high-quality bonds: balance between income and rate sensitivity

- Long-term bonds: can help in some recessions but can hurt in rapid rate rises

- Lower-quality / high yield: can behave stock-like in stress (not a substitute for safety)

In 2026, a lot of confusion comes from people holding “a bond fund” without knowing how sensitive it is to rising rates. If you want less surprise:

- keep bond duration modest (short-to-intermediate)

- keep credit quality high for the “stability” portion

Cash is not a failure — it’s your decision insurance

Beginners often hear: “Cash drags returns.”

True… and incomplete.

Cash also:

- keeps you from selling stocks to pay bills

- gives you emotional breathing room

- lets you buy more when markets are down (if you choose to rebalance)

A practical way to size cash (no fancy spreadsheets):

- Minimum: 3–6 months essential expenses (if your income is stable)

- More: 6–24 months (if income is uneven, you have dependents, or big near-term plans)

Cash isn’t there to beat inflation. It’s there to prevent a dumb forced move.

Rebalancing: one rule, done forever

Rebalancing is the opposite of chasing. It’s “buy low / sell high” in a boring, repeatable way.

You only need one rebalancing method. Pick the one you’ll actually follow.

Option A: Calendar rebalancing (easiest)

- Check twice a year (e.g., January + July)

- If you’re off target meaningfully, rebalance back

Option B: Band rebalancing (more precise, still simple)

- Set a drift band (example: ±5% around your target)

- Only rebalance when an asset breaks the band

Beginner tip: if you’re the type who overthinks, calendar rebalancing is safer. It prevents you from turning your portfolio into a daily project.

“Honest” diversifiers: define the job, accept the trade-off

A diversifier is only useful if it has a clear purpose. And every diversifier has a price — sometimes fees, sometimes underperformance in bull markets, sometimes complexity.

Here are diversifiers that can be honest (if you use them correctly):

Inflation-aware bonds (where available)

- Job: help when inflation is stubborn

- Trade-off: may lag in some regimes; still has rate sensitivity

Gold

- Job: potential crisis/inflation perception hedge

- Trade-off: no cash flow; can underperform for long stretches

Commodities

- Job: tends to respond to inflation and supply shocks

- Trade-off: volatile; not a “set and forget” feel for many beginners

Trend / managed futures

- Job: can help in certain fast-moving crisis periods

- Trade-off: can feel frustrating and “wrong” in calm bull markets; fees/implementation matter

Crypto (only if you insist, and only as an experiment)

- Job: speculative optionality; sometimes behaves differently than traditional assets

- Trade-off: extreme drawdowns; operational/security risk; high emotional load

The beginner rule: diversifiers should be small until they prove they fit your behavior.

If a diversifier makes you check your portfolio more often, it’s already costing you something.

A simple “core + optional diversifier” template you can actually run

Here’s a structure you can adapt without trying to be clever:

- Core growth (stocks): your long-term engine

- Core stability (bonds): intentionally chosen for rate sensitivity and quality

- Life buffer (cash/short-term): sized to your reality

- Optional diversifier: small, clear job, reviewed calmly

That’s it.

If you get this right, you’ve already done the hard part: building a portfolio that can survive your own emotions. Next, let’s turn this into step-by-step action paths you can complete without turning investing into a second job.

Starter action paths: build your 2026 portfolio in days, not months

You don’t need a perfect plan. You need a usable plan — and you need to start.

Pick the path that matches your time and your current stress level.

If you have 30–60 minutes today

Your goal today is not “optimize.” Your goal is “remove the biggest beginner risks.”

- Write your “Soon Money” list (0–24 months).

- rent/mortgage buffer

- debt payments

- known upcoming costs

- emergency fund target

- Decide your cash/short-term reserve number.

- Put it somewhere boring and liquid.

- This is not your investment portfolio. This is your safety layer.

- Pick a simple core allocation you can live with.

A quick rule-of-thumb:- More long timeline + strong stomach → more stock

- More near-term needs + low stomach → more bonds/cash

- Choose one rebalancing rule.

- “Twice a year” is enough.

- Automate one thing.

- automatic contribution (even small)

- or a monthly reminder to invest

Done. That alone puts you ahead of most people who stay stuck in research mode.

If you can do 2–3 hours/week for one month

This path helps you build a real “mini investment policy” without getting academic.

Week 1: Build your one-page plan

- Why you’re investing (1–2 goals)

- Your time horizon

- Your “quit point” drawdown estimate

- Your Soon Money buffer decision

Week 2: Build the core

- Choose your stock exposure (broad, diversified)

- Choose your bond exposure (short/intermediate focus if unsure)

- Set your target weights (use ranges if you’re nervous about precision)

Week 3: Add your rule system

- Rebalancing method

- Contribution schedule

- What triggers a change (life changes only)

Week 4: Optional — add one diversifier, only if it has a job

- One diversifier max

- Small size

- Clear reason it exists

- Clear “how it behaves on a bad day”

At the end of the month, you should be able to explain your portfolio to a friend in 60 seconds without feeling like you’re reciting a spell.

If you already have some experience (and a messier portfolio)

This is a cleanup path. The goal is clarity and control.

- Run a holdings audit (30 minutes).

Group everything into:- stocks

- bonds

- cash/short-term

- diversifiers

- speculative/experimental

- Kill redundancy.

If two holdings do the same job, keep the simpler/cheaper one. - Check duration and credit risk in your bond sleeve.

Many “balanced” portfolios are accidentally long-duration or accidentally heavy in credit. - Set rebalancing rules that prevent tinkering.

If you’ve been changing things often, pick calendar rebalancing to reduce “decision addiction.” - Cap experiments.

If you like crypto or themes, keep them small enough that you can ignore them for six months.

If you’re overwhelmed (the “one decision at a time” plan)

If investing makes you freeze, here’s the simplest sequence:

- Build emergency cash.

- Start one broad stock fund contribution (small is fine).

- Add bonds only if you need stability or you’re close to using the money.

- Add diversifiers only after you’ve stayed consistent for 6–12 months.

This path is boring — and it works because it avoids the biggest beginner killer: stopping and starting.

Okay. Now let’s make this even more concrete with two real-world investor scenarios — same markets, different lives, different “right” answers.

Quick scenarios: two investors, two different “right” allocations

A good portfolio is not “aggressive” or “conservative.” It’s appropriate.

Here are two investors who both want to invest responsibly in 2026 — but they should not use the same allocation.

Scenario 1: 27 years old, stable income, high savings rate

Profile

- Stable job, strong income growth potential

- Can invest for 10–20+ years

- High savings rate (big buffer)

- No big known expenses in the next 2–3 years

What beginners like this often do wrong

- Go 100% stocks because it sounds brave

- Add trendy diversifiers quickly (crypto, themes, “AI funds”)

- Assume they’ll “just hold” during a crash (until the crash happens)

A more realistic allocation approach

- Stock-heavy core (because time horizon is long)

- Bonds present but not oversized (stability, not performance chasing)

- Cash buffer for life events (even if smaller)

How this investor can keep it simple

- Core:

- mostly stocks (broad)

- some bonds (high-quality)

- small cash buffer

- Rules:

- contribute automatically

- rebalance on a schedule

- no new asset classes for 6 months while building consistency

Why this works

This investor doesn’t need a complex hedging system. Their edge is:

- time

- savings rate

- ability to keep buying through downturns

Realistic outcome

They still experience drawdowns. But because the plan is understandable and the buffer is strong, they’re less likely to panic-sell — and that’s the real win.

Scenario 2: 52 years old, uneven income, big near-term obligations

Profile

- Income is variable or less predictable

- Wants to protect lifestyle and avoid forced selling

- May have tuition, family obligations, or a planned purchase in 1–4 years

- Retirement planning is real, not abstract

What beginners like this often do wrong

- Take more risk because they “need higher returns”

- Put down-payment money into stocks “just for a year”

- Buy illiquid products because they look stable

A more realistic allocation approach

- Clear separation of Soon Money vs Later Money

- Larger cash/short-term reserve (to prevent forced selling)

- Bonds chosen to reduce rate shock risk (short/intermediate focus)

- Stocks still included for growth, but sized to avoid panic decisions

How this investor can keep it simple

- Build two buckets:

- Soon Money (0–3 years): cash + short-term bonds

- Later Money (3+ years): balanced stock/bond mix

- Rule:

- never invest Soon Money in volatile assets

- rebalance calmly twice a year

Why this works

When goals are deadline-driven, the biggest risk is not missing out on upside.

The biggest risk is being forced to sell at the wrong time.

Realistic outcome

Returns may be lower than the 27-year-old’s plan — and that’s okay. The goal here is a high probability of meeting obligations without portfolio chaos.

You’ll notice something important: these two investors can both be “doing it right” while holding very different portfolios. Which brings us to the final memory hook: the six decisions to remember when markets start acting weird again.

The 6 decisions you should remember next time markets get weird

When markets get strange, most people look for a new prediction. A better move is to return to a small set of decisions that keep you grounded.

Decision 1: “What problem am I solving — and is it a life problem or a market problem?”

If you’re changing your allocation because your goal changed (new job, baby, home plan), that’s valid.

If you’re changing your allocation because you feel scared after a headline, that’s usually a signal to tighten your rules, not to redesign the whole portfolio.

Do this next

- Write the reason for any allocation change in one sentence.

- If it’s not a life change, wait 72 hours.

Decision 2: “Do I need liquidity soon?”

This is the question that prevents the most beginner pain.

If you need money soon, your allocation should prioritize:

- stability

- short duration

- clarity

Do this next

- Separate Soon Money and Later Money.

- Never force deadline money to take stock-level risk.

Decision 3: “Do I understand my bond risk (duration + credit)?”

When bonds surprise people, it’s usually because they didn’t know what kind of bond risk they owned.

Do this next

- Identify whether your bond sleeve is short, intermediate, or long.

- Identify whether it’s high-quality or credit-heavy.

- If you’re unsure, simplify toward high-quality short/intermediate.

Decision 4: “Am I chasing a diversifier, or assigning it a job?”

Diversifiers are not trophies. They’re tools.

Do this next

- For any diversifier, answer:

- “When does it help?”

- “When does it hurt?”

- “How much am I willing to underperform in calm markets to potentially help in stress?”

If you can’t answer, keep it out (or keep it tiny).

Decision 5: “What’s my rebalancing rule — and will I actually follow it?”

If you don’t have a rule, your emotions will volunteer as the rule.

Do this next

- Pick one: calendar (twice a year) or bands (±5% drift).

- Put it on your calendar right now.

Decision 6: “Is my plan robust, or does it require me to be right?”

The most dangerous portfolios are the ones that only work if a prediction comes true.

A robust portfolio:

- makes sense across multiple futures

- is easy to explain

- is easy to rebalance

- is hard to sabotage with one emotional decision

Do this next

- Replace precise targets with ranges.

- Cap experiments.

- Keep the core boring.

If you take nothing else from this article, take this: investing doesn’t reward the person with the best theory. It rewards the person who can follow a decent plan for a long time — especially when it’s uncomfortable.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational and informational purposes only and reflects general principles about asset allocation. It is not financial advice, investment advice, tax advice, legal advice, or a recommendation to buy or sell any security, fund, or digital asset.

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Any examples, rules of thumb, scenarios, or allocations discussed are simplified and may not apply to your personal situation.

Before making investment decisions, consider your own financial goals, time horizon, risk tolerance, liquidity needs, and constraints (such as taxes, fees, and access to products). If you’re unsure, consult a licensed financial advisor or qualified professional who can evaluate your full circumstances.

Any mention of third-party platforms, providers, or trademarks is for reference only and does not imply endorsement.

If this article saved you time, money, or a headache, you can support my work by buying me a coffee ☕💛

It helps me keep writing practical, no-hype guides like this—thank you! 🙏✨

👉 Buy me a coffee: https://timnao.link/coffee